GW&K Global Perspectives: Russia's Invasion of Ukraine: Key Issues for Global Markets — March 2022

Highlights:

-

As the tragic human consequences of Russia's aggressive invasion of Ukraine unfold, we can only guess as the intermediate longer-term economic and financial market implications.

-

Barring a rapid and humiliating retreat by Russian forces, the invasion looks like the most severe geopolitical shock since 9/11. Risks to global growth have risen accordingly.

-

Key risks include interruption of energy supplies, especially for Europe, as well as a host of “unknown unknowns” regarding the ultimate end game for Vladimir Putin.

Pariah Russia, Pariah Putin

Vladimir Putin’s unprovoked invasion of Ukraine has shocked the world. As a result, Russia and its leader have rapidly assumed pariah status and face a host of severe economic sanctions from the U.S., Europe, and many major nations.

Although developments in Ukraine remain in a state of rapid flux, the invasion is likely to go down in history as a major geopolitical shock that raises serious questions about possible paths the conflict may take:

-

Will Putin succeed with his plans for regime change or annexation of Ukraine?

-

Will “success” for Russia result in an extended political and economic quagmire, including an extended insurgency along with Iran-style economic isolation enforced by Western sanctions?

-

Will Putin respond to sanctions and Western military aid to Ukraine by suspending energy exports, or will Western nations severely curb Russia’s energy exports?

-

Will Putin risk direct confrontation with NATO through possible military confrontations with Poland or the Baltic Republics, including with American forces in those countries?

-

Might Putin himself become subject to regime change by highly placed Russians who are alarmed at where he has led the nation?

-

While Russia distracts the world, will China be tempted to invade Taiwan? Or will China play a constructive role in persuading Putin to stand down?

Anyone who claims to have the answers to such questions has a much better crystal ball than we do. What is clear is that geopolitical risks have risen by an order of magnitude in just a few days. And that creates forces that could dampen global economic prospects for the duration of the conflict and perhaps longer if the war signals a sudden transition to a new, more dangerous, and unpredictable global security environment.

How have stock markets responded to major geopolitical shocks in the past?

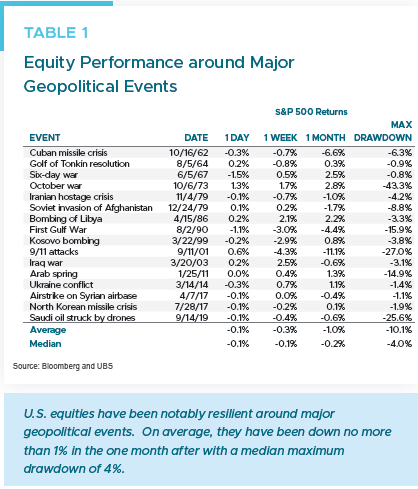

For investors, it is worth keeping in mind that the stock market has been surprisingly resilient to geopolitical shocks in the past. For example, UBS compiled a list of 16 major geopolitical events since the 1960s including events like the Cuban missile crisis, the First Gulf War, and the 2014 Russia-Ukraine conflict (Table 1).

Their data shows that:

- The S&P 500, on average, was down no more than -1% in the one month after; and

- The median maximum drawdown was just -4%

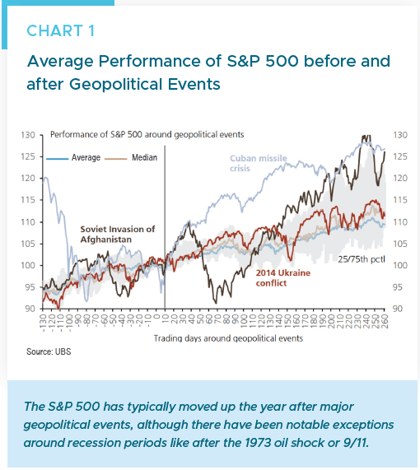

UBS also charted the average performance of the S&P 500 before and after those events, showing that markets typically recovered relatively quickly and went on to post new highs over the following year (Chart 1).

J.P. Morgan did a similar analysis looking back at 12 geopolitical events going back to the October 1973 Arab-Israeli war and oil embargo. Their data showed the average duration of market selloffs was 12 days, with the average selloff being -6.5%, and the recovery taking about 137 days.

Other analysts have pointed out that the economic context around the geopolitical shock eventually dominates the market trend. For example, the S&P 500 was down sharply in the 12 months following both the October 1973 oil embargo and the 9/11 attacks, reflecting the fact that the economy was in recession around those times as well. The actions of the Fed are of course a critical part of the context since recession risks have tended to rise when the Fed has been focused more on fighting inflation than supporting growth.

Are there fundamental reasons the U.S. market should be resilient to the Russia shock?

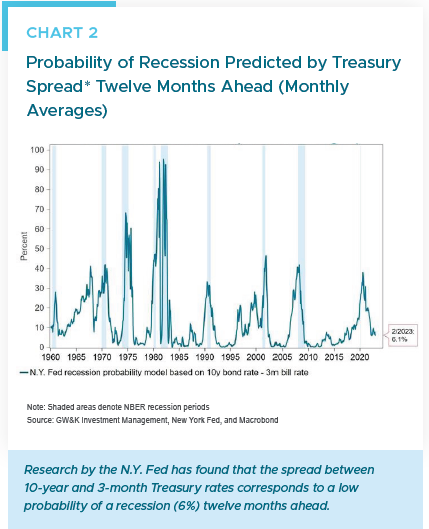

To be sure, there is no guarantee of market resilience in the wake of the current Russian invasion shock, even if historical patterns suggest resilience. It is helpful, however, that the American economy’s economic momentum going into this crisis was very solid, with nominal GDP expected to be up nearly 8% from a year ago in the current quarter and with the corporate sector generally reporting healthy earnings trends. A variety of indicators, such as the New York Fed’s Recession Probability Index, suggest the risk of a recession over the next year is low (Chart 2).

It is also helpful that the American economy has minimal direct exposure to Russia’s economy, which is likely to be hammered by severe sanctions. According to an estimate by Bank of America/Merrill Lynch, Russia contributes only 0.1% to the sales of S&P 500 companies. So a sharp drop in trade with Russia should account for little more than a rounding error on U.S. corporate earnings.

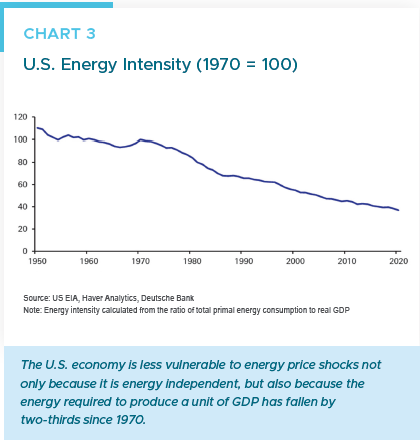

Moreover, America is less sensitive to oil price shocks than it was in the past for two reasons. First, the amount of energy needed to produce a unit of GDP has declined by about two-thirds since 1970, thanks to greater efficiency and shifts in the composition of the economy toward service industries (Chart 3). Second, thanks to the shale oil revolution America has become energy independent. That means that rising energy prices cause a transfer of income from energy consumers to energy producers, which helps limit the negative effect on the overall economy.

How will the Russia shock affect Fed policy?

This topic figured prominently in Fed Chair Jerome Powell’s semiannual testimony to Congress in early March. Not surprisingly, he acknowledged the uncertainty that this development has created and the need “to be nimble in responding to incoming data and the evolving outlook.”

While calling the Russian invasion a “game changer” that could have long-lived effects, he was careful to note that it is too early to say what the real effects will be on the economy. He added that “there will be upward pressure on inflation at least for a while” and made reference to a rule of thumb that each $10 increase in the price of oil per barrel can add about 0.2 percentage points to inflation.

He was very clear that he thought it was appropriate to begin raising interest rates at its March policy-making meeting amid high inflation, strong economic demand, and a tight labor market. He signaled his preference to begin the rate-hiking cycle with a 25 basis point hike in the federal funds rate, but did not rule out moving more aggressively at a “meeting or meetings” beyond that if price increases come in higher than expected or persist longer than expected.

Chair Powell also noted that, before geopolitical events ratcheted up, he had seen a policy path this year in which every FOMC meeting was a possibility for a rate hike and that the Fed would also make progress toward shrinking its balance sheet.

Against that backdrop, his key point regarding the geopolitical situation was this:

"The question now really is, how the invasion of Ukraine, the war, the response from nations around the world - including sanctions - may have changed that expectation. It's too soon to say for sure, but for now I would say that we will proceed carefully along the lines of that plan."

In short, by sticking with the basic plan that had evolved before the Russian invasion, the Fed is attempting “to avoid adding uncertainty to what is already an extraordinarily challenging and uncertain moment.” That said, by emphasizing flexibility and a focus on incoming data, the Fed chair left the door open to implementing additional rate hikes more slowly if it turns out that geopolitical factors are dampening economic activity. At the same time, he left the door open for more aggressive policy if necessary.

Has Fed tightening affected markets differently in high-inflation vs low-inflation periods?

Given Chair Powell’s framing of the Russia shock and his intention to get inflation “back under control,” it is worth looking at the history of Fed rate-hiking cycles to get a sense of how financial markets have responded. We can also look back at periods when geopolitical uncertainty intersected with high inflation and Fed tightening for clues regarding the current environment.

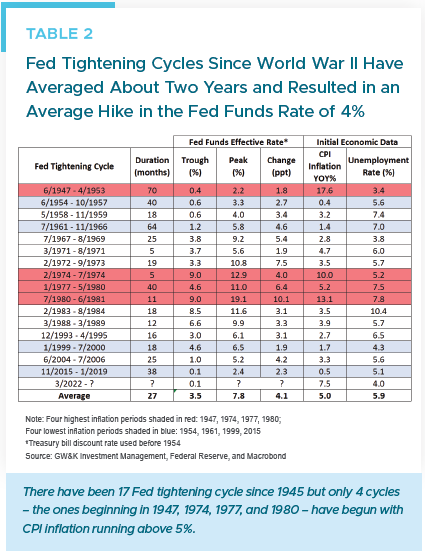

Looking at 17 rate hiking cycles since World War II, we can see that the average cycle lasted about two years (27 months) and saw an increase in the federal funds rate of about 4% (Table 2).

Not surprisingly, three out of the four cycles that had the highest CPI inflation rate when the Fed started tightening were in the 1970s or early 1980s.

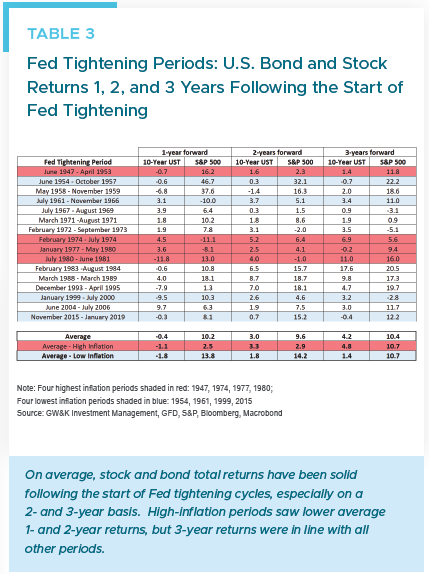

It is encouraging to see that the S&P 500 has delivered annual total returns of close to 10% on average in the one-, two-, and three-year periods following the beginning of Fed rate hikes (Table 3).

This probably reflects the fact that the Fed rate-hiking cycles typically occur when economic growth is providing a positive tailwind to corporate earnings.

Bonds often posted modest losses on a one-year basis, but posted positive two-year returns in 16 out of 17 periods, and posted positive three-year returns in 14 of 17 periods. In short, after brief periods of negative total returns as yields moved higher during Fed rate hiking cycles, bonds usually played their normal role of providing moderate returns while protecting investor capital.

Focusing on the four highest CPI inflation periods, it is worth noting that one- and two-year returns were disappointing on average but three-year average returns were roughly in line with those of all 17 rate-hiking cycles. Note the difference for high-inflation periods depending on the time horizon:

-

1-year returns were -1.1% for bonds and +2.5% for stocks

-

2-year returns were +3.3% for bonds and +2.9% for stocks

-

3-year returns were +4.8% for bonds and +10.7% for stocks

In general, higher inflation pressures require the Fed to be more aggressive in raising rates and also in risking recessions to curb inflation pressures.

We were reminded of that history when Senator Richard Shelby recently asked Fed chair Powell whether he, like Paul Volcker in the early 1980s was willing to “do what it takes, without any reservations, to protect price stability.” Powell replied yes, but then stressed his belief that the Fed can bring down inflation without triggering a recession.1

What are key global economic risks to monitor?

Despite the high degree of uncertainty created by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, a number of key economic risks to the global economy stand out.

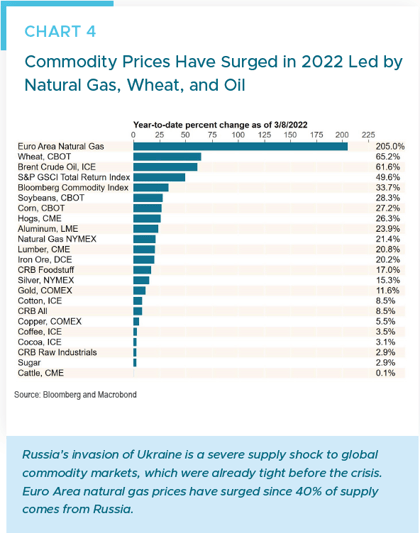

First, there is the supply-side shock to global commodity prices created by the sudden interruption of commodity exports ranging from energy to agricultural commodities. Following the best year in two decades for the S&P GSCI Commodity Index, it has surged by 50% in little more than two months this year (Chart 4). There have been stunning rises in the price of Euro Area natural gas (+205%), wheat (+65%), soy beans (+28%) and corn (+27%). This is already putting further upward pressure on inflation rates around the world, and related pressure on central banks to respond with higher rates.

Second, there is the unique vulnerability of the Euro Area’s economy to consider. The Euro Area depends on Russia for about 40% of its natural gas supply and 25% of its oil supply. Before the crisis struck, the Euro Area was beginning to recover from the pandemic and expected to grow a healthy 4% this year. But Deutsche Bank economists recently warned that a sustained spike in energy prices could trim as much as 3% off of this year’s growth rate. Moreover, it is difficult to factor in the shock to business and consumer confidence that could occur if the Euro Area has to contend with a massive humanitarian crisis involving millions of refugees. The euro has already fallen about 3.5% against the U.S. dollar on the view that the crisis will force the European Central Bank (ECB) to keep negative rates in place for an extended period even as the Fed is hiking rates.

Third, although America’s energy independence makes it less vulnerable than Europe, America’s growth could still suffer if the conflict escalates and the West cuts off most of Russia’s energy exports. The Bank of America’s research team recently estimated that in such a scenario the world could face a shortfall of 5 million barrels per day and a $200/barrel oil price, even if there is some offset from the release of strategic reserves and some increase in OPEC exports. While emphasizing that this is a scenario, not a forecast, they suggest that the hit to U.S. GDP could be as large as 2%.

Finally, just as physical pipelines and supply chains are disrupted by war, global payment chains can be disrupted as well with potential unpredictable consequences. For example, the sanctions on Russia’s central banks and other financial institutions could result in serial defaults on Russia’s external debt, which stood at $490 billion as of the third quarter of 2021. And while Russia has almost no holdings of U.S. Treasury debt, it is estimated to be a $200 billion force in the FX swaps market.2 How these contracts – and related derivative positions – will be handled in the face of sanctions remains unclear. But the potential for unintended consequences of the sanctions in global funding markets cannot be ruled out.

This potential issue reflects the incredible complexity of the global financial system’s “plumbing,” whereby failed trades by some players can create a chain reaction of failures by others. We are confident that these issues will be closely monitored by central bankers, who are likely to respond with emergency liquidity facilities to deal with sanctions-related funding stresses.

Conclusion

When Russia invaded Ukraine on February 24, the world we knew changed decisively, and not for the better. We cannot exclude scenarios that bring a quick resolution to the conflict, like regime change in Russia or China pressuring Russia to come to the peace table. But to use former U.S. defense secretary Donald Rumsfeld’s terms, the list of “known unknowns” as well as “unknown unknowns” has soared. Unfortunately, the scope and duration of the conflict remain unpredictable.

Against this backdrop, investors are likely to focus on the global impacts of higher commodity prices and their impact on inflation, economic growth, and central bank policies, while also keeping a wary eye on the ripple effects of sanctions on financial flows. For investors, times like these clearly highlight the importance of prudent diversification as well as an awareness that markets have typically been resilient in the past to both geopolitical shocks and central bank tightening cycles.

William P. Sterling, Ph.D.

Global Strategist

1. Christopher Rugaber, “Fed’s Powell: Russia’s War on Ukraine Will Worsen Inflation,” Associated Press, March 3, 2022.

2. Gillian Tett, “War in Ukraine Threatens the Global Financial System, Financial Times, March 3, 2022.