From Diabetes Drugs to Investment Megatrend:

When Will GLP-1 Drugs Transform Our World?

GLP-1 agonists are a promising new class of drugs for the treatment of type 2 diabetes, obesity, cardiovascular risk, kidney disease — and potentially neurological and cognitive problems, from Alzheimer’s to impulse control. The drugs have made headline news since they were approved for weight loss, and there has been no shortage of speculation about how their effectiveness will affect investors. Analysts are predicting slowdowns in several areas and some stocks in those categories have taken a nosedive, from snack makers and restaurants to companies that make medical devices that help with a host of obesity complications, such as sleep apnea.

Has Wall Street had too much of a knee-jerk reaction, or will these drugs put an end to obesity and truly change the world as we know it, including the longer-term investment landscape? Equity Analysts Gaby Greenman and Rob Shea share their thoughts.

Q: Do you think these drugs will have a meaningful impact on our lives?

Gaby Greenman: We don’t yet know how these drugs will affect consumer behavior over the long-term, but if some of the assumptions pan out, they could have major implications on a host of diseases.

Almost 70% of US adults are overweight, and 42% are obese. Obesity is a serious chronic illness that dramatically increases the chances of developing further diseases, like heart disease, type 2 diabetes, kidney disease, and some cancers. If these drugs can cure the obesity epidemic, there will be many economic implications, including for the consumer and health care companies.

In addition to being touted as the most effective and safest weight loss drugs in history, these drugs may be able to treat some cardiovascular issues and kidney diseases, and potentially allow for better impulse control and memory formation. There is a lot left to understand about the full range of effects these drugs may have.

Q: Which drugs are available for use now, and how do they work?

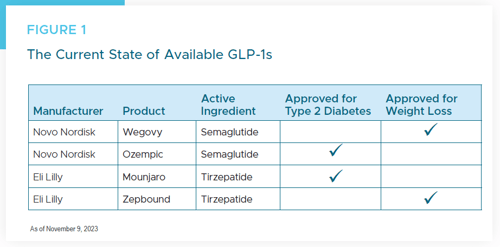

Rob Shea: There are four GLP-1 drugs on the market today: Ozempic and Wegovy, from Novo Nordisk, and Mounjaro and Zepbound, from Eli Lilly. Both drugs that have been approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in the US to be prescribed for weight loss are effectively the same drug their makers’ produce for treating diabetes (Figure 1).

Glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) is a naturally occurring hormone that is produced after eating that stimulates the release of insulin, suppresses the release of glucagon, slows down the emptying of the stomach, and reduces appetite. GLP-1 agonists are a class of drugs, including semaglutide, that mimic the effects of these hormones.

Tirzepatide is a dual agonist that targets both the receptor for GLP-1 and the receptor for glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP), another hormone released after eating. It works similarly to GLP-1. It is possible that tirzepatide, with its dual action, may prove to be more effective than semaglutide for lowering blood sugar and promoting weight loss.

Q: How effective are these drugs for weight loss?

Gaby: Obese patients taking these drugs for a year have lost between 10% to 30% of their body weight. A 20% reduction in body weight is similar to results from having gastric bypass surgery. These are meaningful results, without an invasive surgical procedure. One caveat is that once patients stop taking the drugs, they do regain weight quickly if lifestyle changes aren’t maintained.

Q: What about side effects?

Rob: So far, the safety data is compelling. Semaglutide has been on the market for treating diabetics for over five years, and the risk/benefit profile is pretty positive today. There are many studies being done with these drugs for many different indications, and all of those will help build a larger safety database. Weight loss specialists and endocrinologists who have been using these drugs since they’ve been approved are still prescribing them, and in most instances reporting side effects like nausea and diarrhea, which can be much more manageable than some of the long-term side effects of being obese.

Q: Do all overweight adults in the US have access to these drugs?

Gaby: Not without a type 2 diabetes diagnosis, unless they want to pay out of pocket — and these drugs are very expensive; upwards of $1,300 per month. Currently in the US, doctors have a code in their databases to prescribe these drugs for the treatment of type 2 diabetes, but not for weight loss. Many health insurers do not cover prescription medications for weight loss, which they consider to be a lifestyle consequence, rather than a disease or genetic problem.

This is why the large number of clinical trials for treating other conditions with these medications is so important. If the drugs can be prescribed and covered by insurance for the treatment of sleep apnea or another condition that is a result of being overweight or obese, that could be a way for patients to get a prescription for GLP-1 drugs and have it covered by their medical insurance — assuming insurers follow suit and cover the drugs for other indications. If the drugs really start alleviating many obesity complications and diseases, they may prove to be cost effective for insurers to cover.

Coverage for these drugs is fairly good right now for people with diabetes, but we’re starting to see that change as demand increases. Some insurers are beginning to put restrictions in place — for example, they will cover the cost of the prescription, but only for patients who have been on a weight management program for six months, or who have tried older, less expensive weight loss drugs first.

Rob: Many doctors want to be able to prescribe these drugs for their overweight or obese patients who have prediabetes, or other health issues. Research indicates that one in six deaths in the US are related to obesity,1 so at some point in the not-too-distant future, it would seem logical for insurers to cover it, at least for the initial period required to lose enough weight to no longer be obese. There are big benefits to that, as that initial weight loss could cause real momentum for patients to maintain a healthy weight. Currently, these medications are only available in injectable forms, but they will likely be in pill form soon, and in different dosages to help more of the population — perhaps there will be a lower dose to help with maintaining weight loss.

In time, the cost of these drugs will come down, and eventually there will be generic forms and biosimilars, too. The next five years will drive competition and production, and, as Gaby mentioned, we may see changes in how healthcare insurers view prescription medication to treat obesity.

Q: When did you start to see an impact from these drugs on the stocks you cover? Are investors incorrectly assessing the effects GLP-1 drugs will have on consumer stocks?

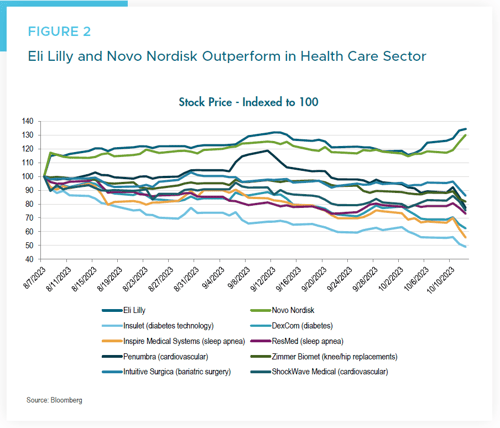

Rob: We really started to see the impact on stocks starting in August, when Novo Nordisk released results from its five-year SELECT study with Wegovy, which targeted cardiovascular outcomes. The study included 17,604 patients from 41 countries who were over 45 years old and overweight or obese with established cardiovascular disease and no history of diabetes. What they found was that participants had a 20% reduction in major adverse cardiovascular events compared with a placebo, and they tolerated the drug well. For a few weeks, it hit medical device stocks hard, and some companies lost a significant amount of value (Figure 2). These are companies that make devices that help patients who have diabetes, or who make devices to help people with sleep apnea — even a surgical company, as the number of bariatric surgeries has dropped since the drugs became popular.

These drugs have decreased alcohol consumption in rats, and we’ve heard anecdotal stories about how they’ve helped users stop compulsive shopping and other addictive behaviors — more studies are needed in these areas. However, there was a chronic kidney disease study that was stopped early because the efficacy was so strong: Participants showed a 30% slower progression of chronic kidney disease. Based on that data, all of the dialysis stocks were down around 20%.

Gaby: A few weeks later, I noticed the effect in many of the Consumer Staples stocks I cover. Because these drugs can cause people to consume 20% fewer calories — and no longer enjoy really salty, sugary, or fatty foods — snack, candy, soft drink, and some alcohol companies saw double-digit losses.2

Q: Do you think the reactions have been appropriate?

Rob: It really varies. Some of it has been because of where the stocks were trading going into it. For example, a medical technology company popular for its surgical intervention for sleep apnea was very expensive, trading somewhere around 12 times revenues. It’s now down to around five times revenues. What’s the right valuation if the total addressable market shrinks? That remains to be seen. Many affected companies are making the case that they will be benefitting from tailwinds because of these drugs. For example, if you’re above a certain BMI, you’re not eligible for surgery. GLP-1s may help some people lose weight so they can have the surgery they need.

We believe we are witnessing a megatrend, with the biggest piece of that being longevity. If life expectancy in the US goes from, say, 83 to 87 that would be significant. And maybe more people would have an improved quality of life in their final years.

Gaby: Another example of a potential tailwind could come for restaurants and food companies in the ability to serve smaller portion sizes and charge the same price, if a meaningful percentage of the population is taking these drugs and then trying to maintain a healthy weight.

I listened to a panel of six people taking the drugs and they said they were consuming smaller portions, and some of them had cut out sugar altogether, because it tasted different. Greasy, fried food also affected their stomachs in a negative way, as did alcohol. So aside from smaller portion sizes, there could be parts of the food pyramid that are negatively or positively impacted by more people taking these drugs.

One in four Americans over 45 take statins to help keep their cholesterol levels down.3 They may have started trying to control it on their own by changing their diets before taking the pill, but if that lifestyle change didn’t bring their cholesterol levels down enough, they started taking the statins and noticed great results. Did they stick to their new, healthier diet? In many cases, no: they continued to eat what they wanted. I think a lot will depend on a person’s dosage, and there will be a lot of variations, but certain categories of food may be impacted more than others.

I am also interested to hear from company management teams about how they are thinking about this potential disruption. I suspect most will not see any effect in their volumes yet because GLP-1 usage is still very low. However, as we’ve seen in the past, many companies are adept at changing formulations, introducing new products, and creating low-calorie options by reducing pack and product sizes. Overall snacking may decrease, but people may just reduce the amount of a particular snack they really enjoy, and not cut it out altogether.

We don’t know how much of the population will take these drugs. But if we say, after 10 years, 10% of the population is consuming 20% fewer calories, that could create a 200 basis point headwind for food consumption over that period. That’s 20 basis points per year — a small enough impact, over a long enough time frame, for companies to figure out how to overcome it.

Q: What could replace that spending — aside from the drug manufacturers, who are the beneficiaries?

Rob: Gyms and protein supplement makers are certainly potential beneficiaries. A possible restriction health insurers may put in place before they’ll cover the drugs could be a required increase in activity levels. People taking the drugs may want to speed up weight loss, maintain their lower weight, and nurture muscle mass — all strong incentives to get more exercise and consume more protein. And for some people, it may be easier to exercise once they’ve lost excess weight.

Gaby: Retail clothing companies could benefit from people needing to refresh their wardrobes as their size changes. But it is difficult to predict timing until we know more; assumptions about the percentage of the population that will be on these drugs within five years are still all over the place. What I’m considering to be the most likely scenarios right now are small impacts over a five- to 10-year period. How many basis points of headwind that equates to will vary, but many companies will be able to overcome that with pricing.

I pay close attention to the large retail chains like Walmart and Target, as many other companies will follow what they do. So far, we haven’t seen big changes at these retailers as a result of the drugs. All we can say with complete confidence right now is that we will be watching closely for whatever changes these drugs will bring for a while.

Published December 2023

1 https://www.colorado.edu/today/2023/02/23/excess-weight-obesity-more-deadly-previously-believed#:~:text=Excess%20weight%20or%20obesity%20boosts,to%20new%20CU%20Boulder%20research.

2 Morgan Stanley Research, “Downsizing Demand: Obesity Medications’ Impact on the Food Ecosystem,” August 7, 2023.

3 Statin Use Is Up, Cholesterol Levels Are Down: Are Americans’ Hearts Benefitting?, Harvard Health Publishing, April 15, 2011.