GW&K Global Perspectives — March 2024

A Welcome Burst in Productivity Growth

Highlights:

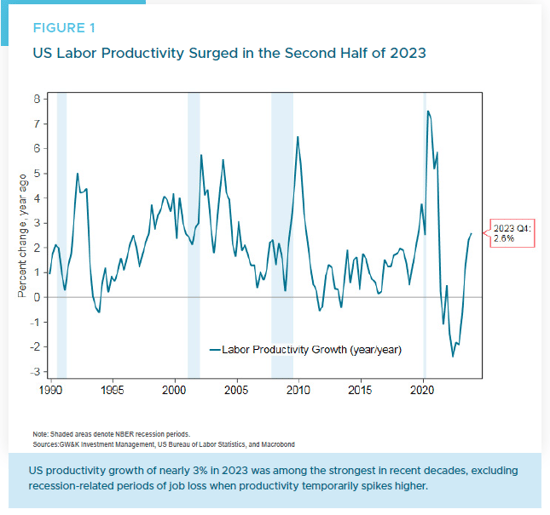

- US productivity surged by nearly 3% in 2023, its strongest growth since the early 2000s, outside of recessions. The biggest driver was not hot new tech, but a notable easing of supply chain pressures.

- Other drivers included government policies, which triggered a reshoring boom in manufacturing construction, and a hot labor market, which pressures firms to boost productivity.

- The jury is still out on how sustainable the productivity surge will be. If it continues, it should support a more accommodative Fed policy, reminiscent of the Greenspan Fed of the 1990s.

A New Wind at America's Back?

Last year saw some extraordinary economic developments. Despite tight monetary policy and an inverted yield curve, the much-anticipated recession never materialized. Instead, real GDP growth surged to a 4.1% annual rate in the second half, even as the Fed’s favored inflation measure moderated to slightly below its 2% target over the same period.

The confluence of stronger growth and lower inflation suggests what economists call a “positive supply shock.” It’s also been called “immaculate disinflation,” with the improved supply picture having the potential to be a powerful force supporting economic growth and job gains in coming years.

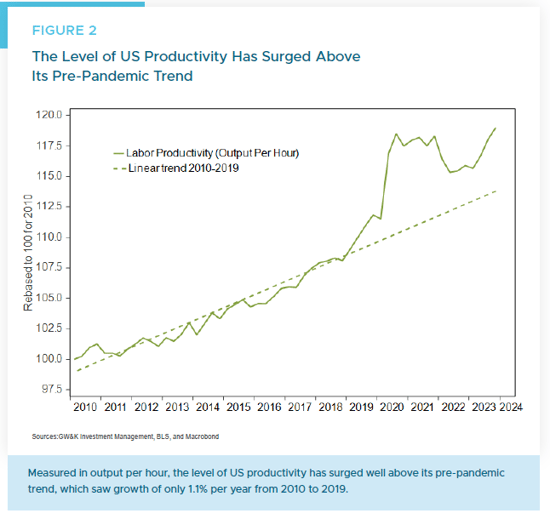

One reflection of improved supply-side developments is recent data showing that US output per hour worked surged by about 3% across the nonfarm economy in 2023 (Figure 1). That is the fastest rate since the late 1990s to early 2000s tech boom, outside of recessions. It outshines the 1% or so averages before the Covid-19 shake-up and what most economists expected as the “new normal,” as aging populations and a dearth of radical innovations kept a lid on economic dynamism (Figure 2).

Why Did Productivity Suddenly Surge in 2023?

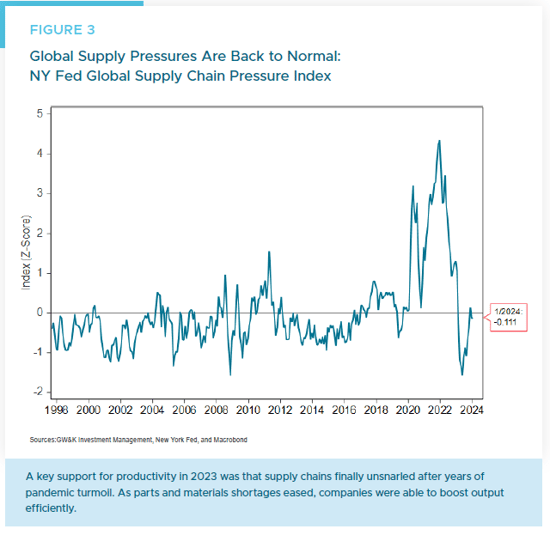

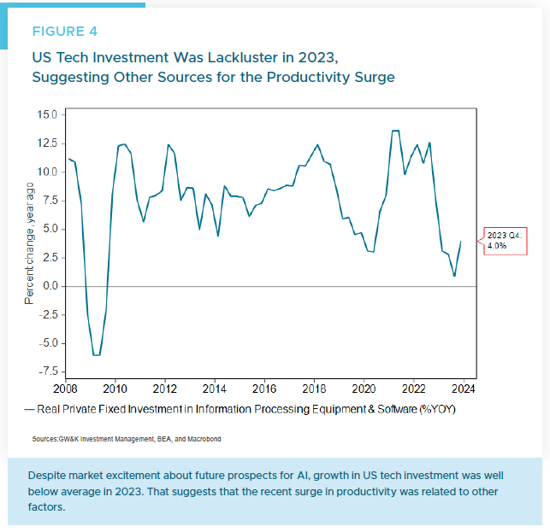

Why the sudden productivity revival?1 To start with, despite understandable enthusiasm in financial markets about the potential implications of the latest wave of AI technologies, we think it is too early to attribute the recent productivity surge to that factor. Indeed, growth in information processing equipment and software was lackluster in 2023, suggesting that other forces were more significant in explaining surging productivity (Figure 3). While recent developments in AI and robotics augur well for future growth in productivity, we believe more mundane forces were at work last year.

First, the alleviation of pandemic-induced supply woes provided a boon (Figure 4). Shortages of components, commodities, and labor that plagued factories in 2021 and 2022 abated. Firms were finally able to obtain the inputs needed to meet still-robust demand eagerly. With fewer bottlenecks impeding production, efficiency improved. This was most visible in makers of long-lasting goods, from cars to computers. But construction also benefited as prices for materials like lumber retreated from dizzying heights.

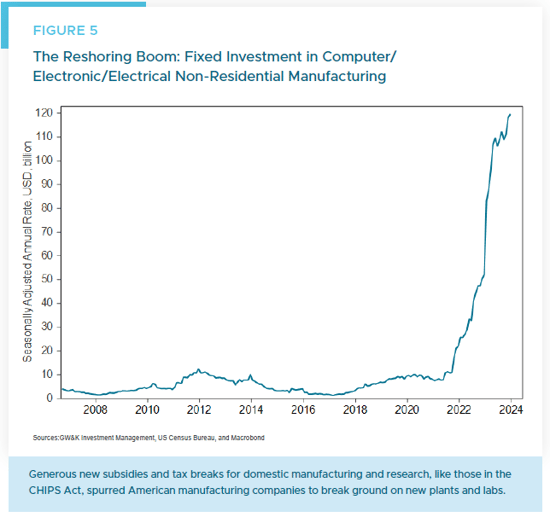

Fiscal policy lent further impetus. Generous new subsidies and tax breaks for domestic manufacturing and research, like those in the CHIPS Act, spurred companies to break ground on new plants and labs (Figure 5). Though these facilities will take years to complete, expectations of swelling investment in productivity-enhancing equipment and structures lifted animal spirits. Moreover, with corporate-tax loopholes now narrowed, some existing profits may have been redirected toward growth-promoting uses rather than financial engineering.

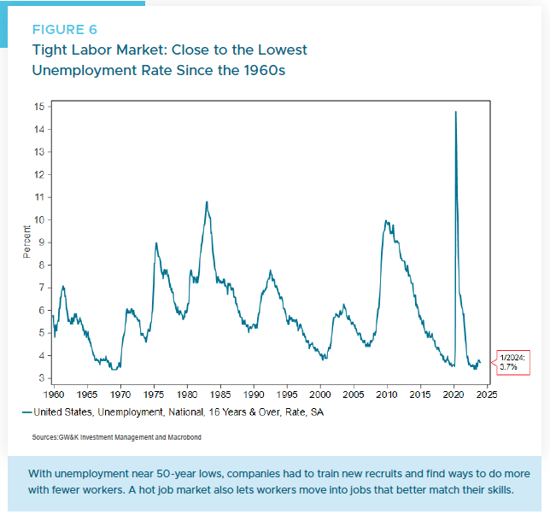

There is also reason to believe that the vigorous job market played a role in lifting productivity. With unemployment near fifty-year lows for an extended period, firms were under intense pressure to effectively utilize relatively scarce labor resources (Figure 6). The tight labor market forced firms to tap previously sidelined groups like the disabled, former convicts, those with gaps in their résumés, and even undocumented immigrants. It also compelled them to train, retain and better deploy employees. Workers gained opportunities to migrate to jobs where their talents proved most valuable.

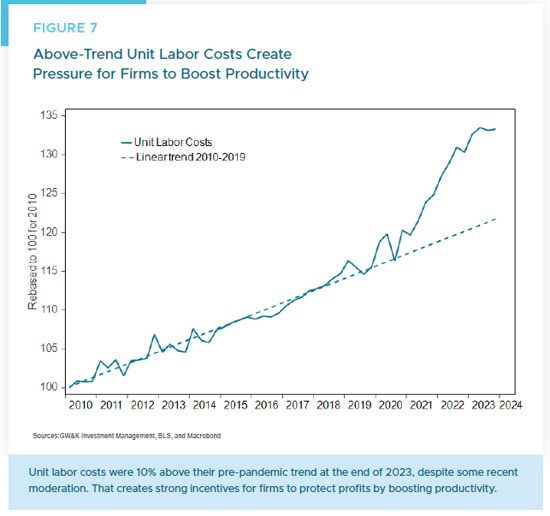

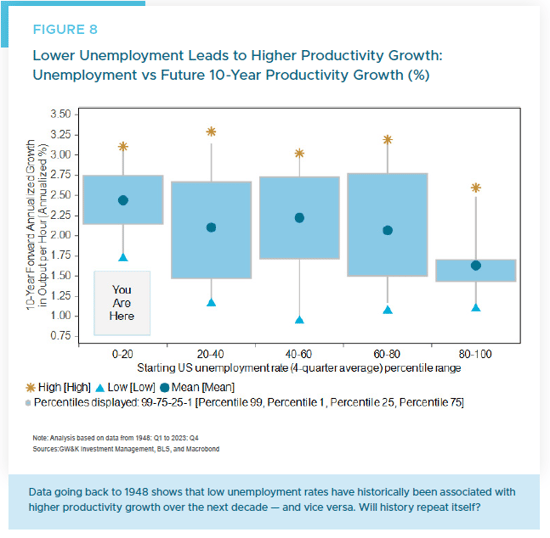

Surging productivity helped the growth in unit labor costs fall from 4.4% in 2022 to only 2.3% in 2023, aiding the Fed’s fight against inflation. But the legacy of the tight labor market in previous years kept the level of unit labor costs at the end of last year 10% higher than the pre-pandemic trend (Figure 7). In order to maintain or boost profit margins despite high labor costs, firms have no choice but to use labor as efficiently as possible. Based on data going back to 1948, there has been a clear pattern of low unemployment leading to higher future productivity growth — and vice versa (Figure 8). Incentives matter and the evidence suggests that low unemployment aids productivity growth.

Could the productivity bounty continue? To a degree, yes. Supply kinks may recur but are unlikely to revisit recent severity, absent a new global catastrophe. Chip-oriented industrial strategies should steadily bear some fruit. Robust economic growth with scant inflationary heat, even as the Fed lifted interest rates, shows room remains before overheating risks arise. New AI “co-pilot” tools are now being deployed by America’s tech giants, which should bear fruit over time as they promote widespread adoption of productivity- and quality-enhancing business processes.

Equally, however, complacency would be misguided. Though technology holds promise, realized investment in new equipment and intellectual property slowed lately rather than accelerated. Public infrastructure spending could yet founder on implementation hurdles. And for all the labor market’s resilience thus far, its workings remain imperfectly understood by policymakers. There exists the peril, still, of the Fed overreacting to recent job gains, short-circuiting the present boom.

Implications for the Fed of a Productivity Revival

The Federal Reserve now faces an intriguing challenge: managing the implications of surging US productivity. This situation, highlighted by recent remarks from Chicago Fed President Austan Goolsbee, may put the Fed in a position reminiscent of the late 1990s productivity boom.2 With inflation under control and robust job and GDP growth figures coming in, the US economy seems to be defying traditional economic models that tie such growth to rising inflation.

This period of strong productivity growth — underscored by significant job additions and a stable inflation rate — suggests we’re witnessing a shift that could allow for a more relaxed monetary policy stance. The Fed now finds itself weighing the possibilities of interest rate cuts in a thriving economy, a move that would have seemed counterintuitive in a different economic context.

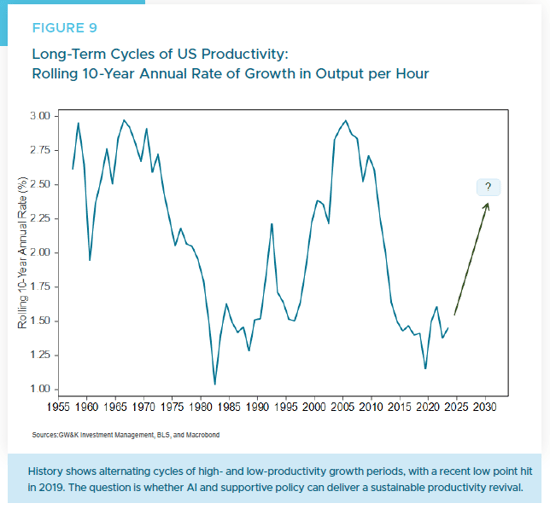

The narrative is compelling. On one hand, the Fed’s cautious approach, as indicated by Jerome Powell’s reluctance to commit to immediate rate cuts, reflects a conventional wisdom: don’t rock the boat if the ship is sailing smoothly. On the other hand, the underlying productivity growth presents a case for potential rate reductions (Figure 9). This growth, driven by real improvements across technology, business models, and policy, suggests that the economy can handle lower rates without spiraling into inflation.

The prospect of cutting rates in such an environment is not without precedent. The late 1990s saw Alan Greenspan’s Fed navigate a similar tech-driven productivity surge with lower rates, fueling significant economic expansion despite fears of a bubble. Today’s Fed, however, must balance these historical lessons with the current economic indicators and the potential for a financial sector impact if rates remain high for too long. This could become a key issue for the commercial real estate market, where vacancy rates remain high and property values depressed.

The market’s expectation of rate cuts adds another layer to this decision-making process. Despite Powell’s cautious stance, the anticipation of easing has been baked into market forecasts, suggesting that businesses and investors are already positioning for a more accommodative policy environment. This expectation, if unmet, could disrupt economic momentum, turning a soft landing into a harder one.

In summary, the Fed’s path forward is delicately poised between embracing the productivity-led growth opportunity and managing the broader economic and financial implications of its policy decisions. As the US economy charts this unusual course, the Fed’s actions will be closely watched for signals of how it plans to navigate the intersecting currents of productivity growth, inflation control, and financial stability.

William P. Sterling, Ph.D.

Global Strategist

1 This analysis relies on detailed work by Skanda Amarnath, “It Wasn’t AI: How Fiscal Supports, Supply Chain Healing, & Full Employment Explain Exceptional Productivity In 2023,” Employ America Blog, January 31, 2024.

2 Michael McKee, “Fed’s Goolsbee Doesn’t Explicitly Rule Out March Cut,” Bloomberg News, February 5, 2024.