GW&K Global Perspectives — February 2024

Is the US Dollar Overvalued?

Highlights:

- After an 11-year climb from 2011 to 2022, the foreign exchange value of the US dollar remains very high by many measures.

- America’s economic strength and the Fed’s aggressive rate hikes support the dollar’s value. America’s tech boom is also attracting global capital.

- As growth slows and the Fed shifts to more dovish policies, some dollar weakness seems likely. History suggests a weaker dollar may persist for years.

The Dollar Stays Strong

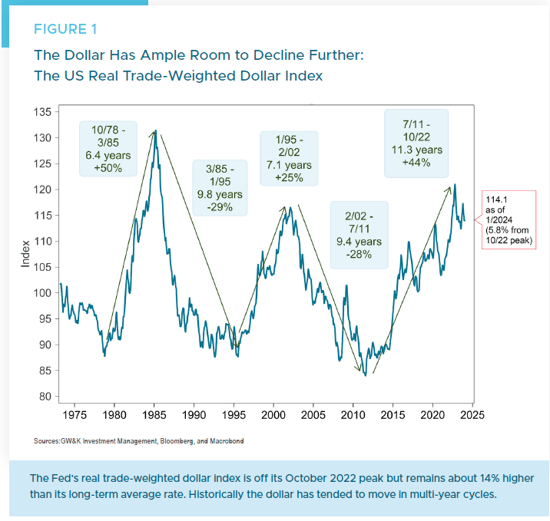

The US dollar fluctuates continuously against other major currencies. One common metric is the Fed’s inflation-adjusted, trade-weighted Real Broad Dollar Index, a weighted average of the US dollar against currencies from key US trade partners (Figure 1).

This index shows multi-year swings in the dollar’s real value. The latest 11-year upswing boosted the dollar’s value 44% from 2011 to 2022. Following a 6% drop from its October 2022 peak, the index remained very high by historical standards in early 2024 (90th percentile since 1973).

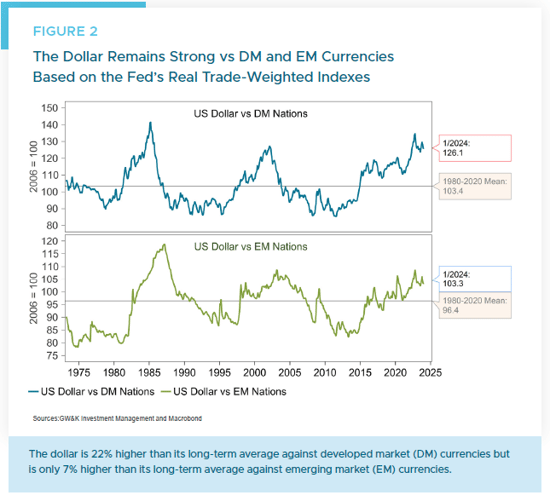

At its January level of 114, the index was 14% above its long-run average of 100. This suggests the dollar may be “overvalued” by about 14%. Breaking this down, the dollar looks more overvalued against developed market (DM) currencies than emerging market (EM) currencies (Figure 2).

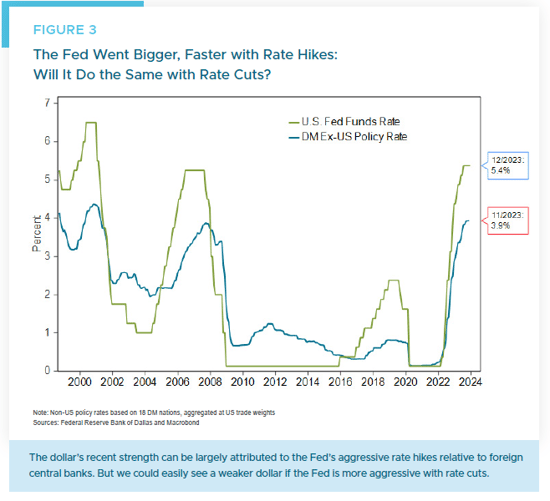

We’ll examine other ways to assess the dollar’s valuation. The takeaway: the dollar looks overpriced by almost any measure, signaling downward pressure ahead. That bias could strengthen if the Fed cuts rates as sharply as it hiked them (Figure 3).

Incidentally, the dollar’s October 2022 peak aligned with the bottom in US stocks. That fits the dollar’s reputation as a “risk off” indicator, with dollar weakness signaling “risk on.”

What Explains the High Dollar?

Forecasting currency values is notoriously difficult. Factors like central bank policies, interest and inflation rate differences, trade balances, and investment flows can all have a major impact.

To simplify, Canadian economist and Nobel laureate Robert Mundell emphasized each nation’s policy mix. Nations with loose fiscal policy and tight monetary policy tend to see rising real interest rates and currency strength. The opposite mix brings declining rates and currency weakness.

Viewed this way, the Reagan-era tax cuts and Paul Volcker’s tight monetary policy drove the dollar’s spike in the mid-1980s. In contrast, loose money after 2001 and especially post-2008 brought dollar declines.

More recently, huge pandemic relief spending, plus supply disruptions, fueled major inflation. The Fed aggressively tightened money in response — channeling Paul Volcker. This textbook recipe lifted the dollar since the Fed hiked rates more sharply than other key central banks.

We’d also note the dollar tends to reflect stock market performance. Markets offering better returns attract more capital inflows. Likely the dollar benefited from investor enthusiasm for AI advances and big tech stock gains. Should the tech rally wane, for whatever reason, the dollar could slip.

Assessing the Dollar Through Burgernomics

Purchasing power parity (PPP) suggests exchange rates should equalize the prices of similar goods across countries. This abstracts from realities like shipping costs and regulations. But it offers insight.

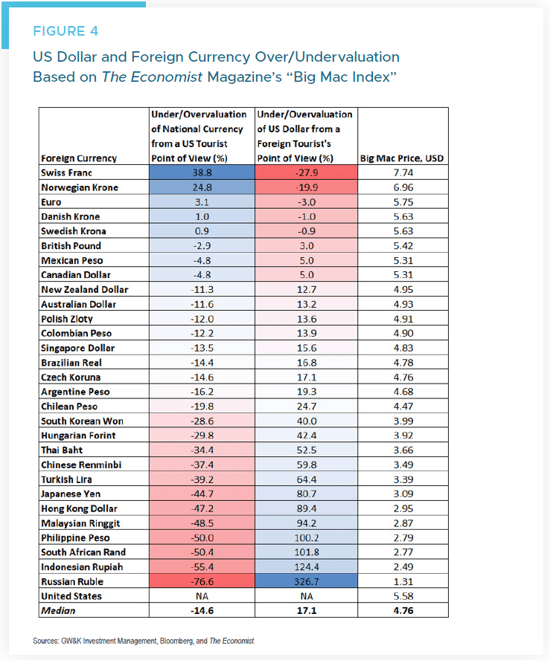

For years The Economist magazine has assessed PPP via The Big Mac Index, comparing burger prices internationally. This determines if currencies are under- or overvalued versus the dollar (Figure 4).

The data show most foreign currencies look undervalued. The median currency is undervalued by about 15%. That corresponds to dollar overvaluation of 17% — remarkably close to our 14% overvaluation estimate earlier.

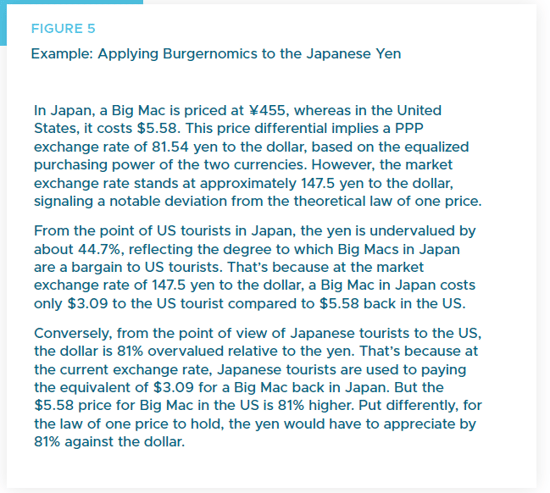

We can view PPP two ways. First, the table shows current exchange rates make Big Macs cheaper abroad for US tourists. Second, it shows how over- or undervalued the dollar is for foreign tourists in the US. Figure 5 explains the math for the Japanese yen.

The IMF's More Comprehensive Data

Like the Big Mac index, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) uses extensive price baskets to calculate PPP exchange rates across countries. However, the IMF approach is far more detailed and complex than comparing burger prices.

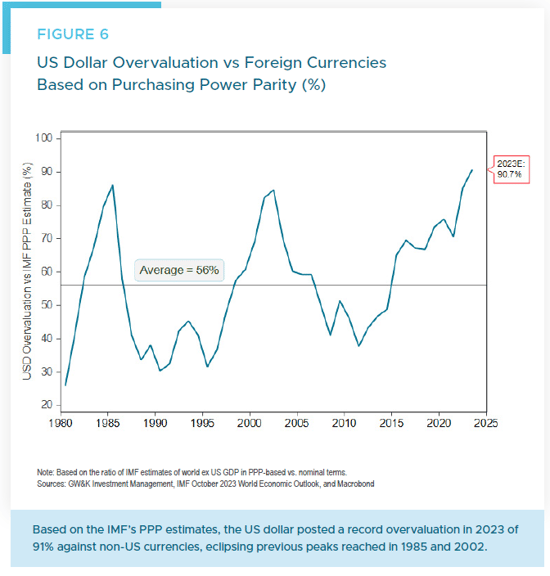

The IMF data indicate the US dollar was 91% overvalued in 2023 — a new record high (Figure 6).

Why does the IMF data show such a high degree of dollar overvaluation? First, IMF data has always shown the dollar to be overvalued, even at past lows. This likely reflects ongoing demand for dollars as the global reserve currency. That stifles PPP and keeps the dollar high.

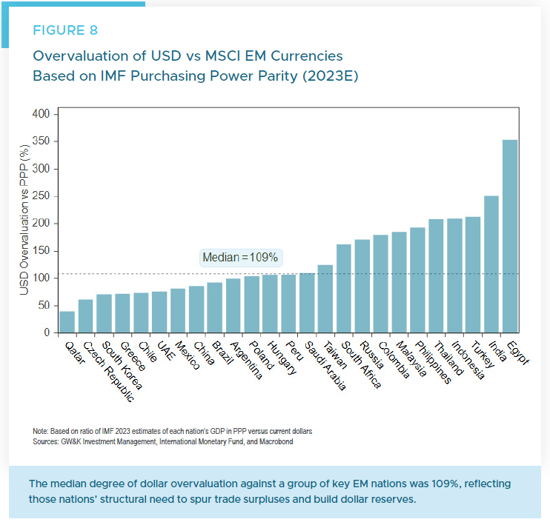

Second, surging emerging market (EM) economies have boosted US dollar overvaluation over time. EM nations often suppress currencies to spur surpluses and build dollar reserves. As a result, the US has run sustained trade deficits to meet dollar demand abroad.

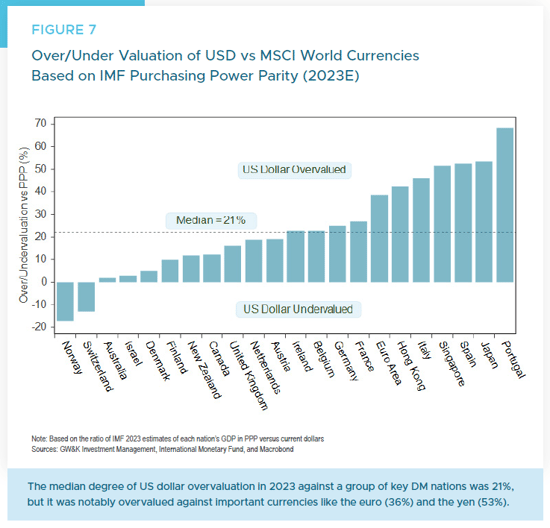

Against key developed markets, the US dollar 2023 overvaluation was 21% (Figure 7). But for

leading EM nations it was 109%, driven by their need to maintain trade competitiveness (Figure 8).

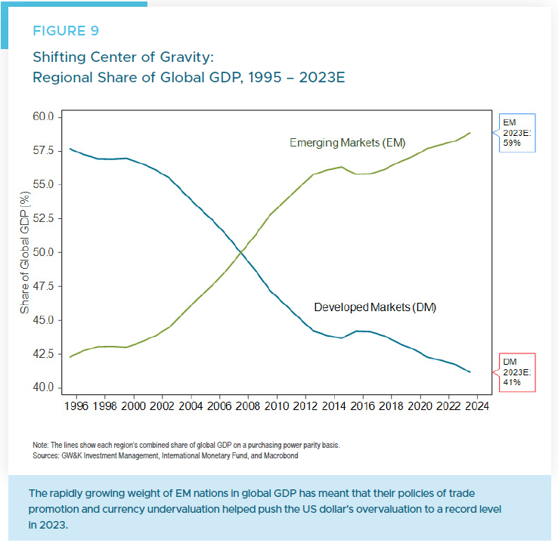

Since 1995, EM nations’ share of global GDP on a PPP basis surged from 40% to 60% (Figure 9).

As this large, undervalued bloc grew, US dollar overvaluation followed.

Conclusion: Dollar Risks are Downside

Much dollar overvaluation is structural due to EM dollar demand for reserves. But the Fed’s recent dovish pivot suggests less support ahead. History also shows the dollar tends to move in multi-year cycles. Given record-high overvaluation, the risks seem tilted toward years of declines.

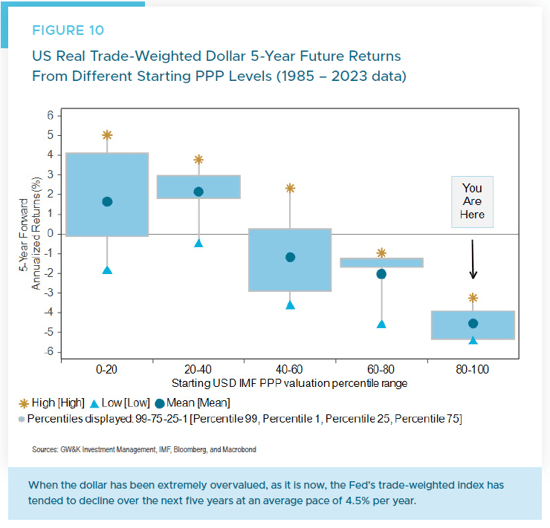

When the dollar has been extremely overvalued on the IMF’s PPP data, the Fed’s trade-weighted index has tended to decline over the next five years at an average pace of 4.5% per year (Figure 10).

There is no guarantee that history will repeat itself. But with the dollar having hit record overvaluation in 2023, it makes the case for international portfolio diversification quite compelling right now from a currency perspective.

William P. Sterling, Ph.D.

Global Strategist