The Trouble with Municipal Bond Benchmarks

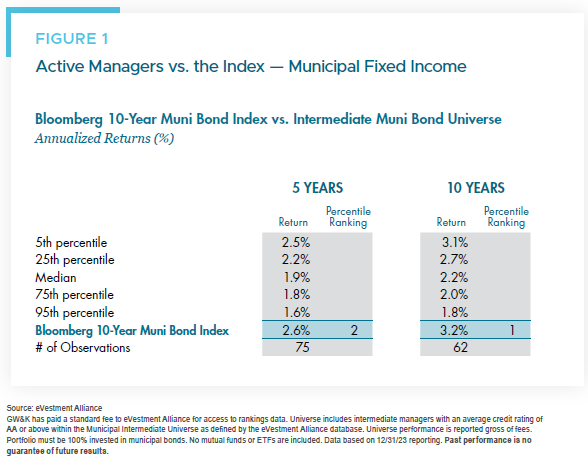

Why do municipal bond managers often fail to outperform their benchmarks? This is a reasonable question given the stellar track record of municipal indexes over basically any longer-term time horizon. In fact, if you look at an index that is supposed to represent the intermediate municipal bond space, the Bloomberg 10-Year Municipal Bond Index, it outperforms more than 95% of managers over trailing five- and 10-year periods (Figure 1).

The Problem: Indexes Are Uninvestable

The biggest issue with fixed income benchmarks is that they fail the most important and obvious test: the ability to purchase the index. Equity investors have the option of ditching their manager and buying an ETF or mutual fund that mimics the S&P 500. Municipal investors have no such alternative. Why is this the case?

The municipal market is a vast, fragmented universe of mostly smaller issues. The number of actual bonds outstanding totals over one million. To create an index, Bloomberg pulls the largest issues based on an arbitrary cutoff, which narrows this group down to approximately 11,000 in the case of the 10-year Index. But this culled down collection of bonds is still impossible to replicate. Even if you had a portfolio with the capacity to buy this many securities (unlikely), you wouldn’t be able to find them because about 99% of municipal securities don’t trade in the marketplace on a given day.1 They have been sold to investors (most of whom will hold to maturity), never to be seen again.

Why Is Index Performance So Strong?

A number of factors play into why municipal bond indexes have such strong relative performance. Many of these elements are not realistic and cannot be implemented by municipal bond managers, including:

No Transaction Costs — Since the municipal bond market has no central exchange, bonds are bought and sold through broker dealers. This reality means that every trade has a cost associated with it, often referred to as the bid/ask spread. While institutional managers with experienced trading desks can minimize these costs, they are still a fact of life for market participants.2 However, the indexes bear no transaction costs. Securities simply flow in and out at the price provided by an evaluation service. These "trades” also have no tax consequences or implications. In a market that is viewed as one of the most inefficient and illiquid, this provides an important difference that cannot be implemented in an actual trading environment.

Excess Yield Through Illiquidity — Because indexes do not have to pay transactions costs, they can invest in the less liquid areas of the market with no consequences. The indexes have substantial positions in sectors that have higher costs to transact, including but not limited to: prepay gas, tobacco, single-site hospitals, Mello Roos (ad hoc California taxes to fund infrastructure projects), industrial development, and small colleges. Municipal bond indexes also contain weighty holdings in BBB-rated bonds and below-market coupons that often receive weak bids, especially in a down market. And when a security gets downgraded to below investment grade, the indexes do not have to offer concessions to find actual buyers. Instead, the offending security merely exits the index at an untested (and likely too high) price deemed appropriate by an evaluation service. Essentially, the indexes get all the benefit of extra yield without any of the significant illiquidity that accompany such risks.

No Cash Drag — Most municipal bonds pay interest every six months. A diversified portfolio will likely have cash flows month to month that earn money market interest that historically yield less than the bonds themselves. However, the index is always fully invested, never has to reinvest any interest payments, and never has cash drag.

AMT Exposure — The indexes include bonds that are subject to the Alternative Minimum Tax (AMT). These bonds provide additional yield because for individuals who fall into the AMT, interest is subject to a 28% rate. The indexes don’t care if you are in the AMT or not, they are going to invest in these securities and pick up the extra yield. Municipal managers typically steer clear of these issues for their clients to avoid the steeply negative tax consequences.

What Does This Mean for All Municipal Investors?

Municipal bond indexes are a frictionless and failed construct. They are at best just a proxy or indicator of a “ball park” estimate for performance. Any investor should have the option to choose between investing with a manager or investing in a representative index. But this is not the case in the vast majority of the fixed income world. These universes are simply too large and there are too many issues to fairly replicate in an actual portfolio.

At GW&K, our goal is to provide the best possible alternative. We have been investing in the municipal bond market for nearly 50 years. We believe an active management approach rooted in disciplined research is the best way to uncover opportunities in this complex market. Unlike an index, our portfolios can be customized and tailored to the individual. For example, we can allocate state-specific securities to client residents, resulting in higher after-tax returns. We are also taking into consideration each client’s tax situation with the ability to take tax losses, an important feature in total-return calculus. Our clients have transparency into their underlying holdings and own their bonds directly. We have the benefit of an institutional trading desk where we scour the market for the securities that can maximize total return while minimizing transaction costs. Our goal is always to perform well against our benchmark index, but a more realistic comparison is our intermediate peer group where our long-term performance is strong.

1See “Best Execution: The Investor’s Perspective,” https://www.msrb.org/sites/default/files/Best-Execution-Investors-Perspective.pdf, from the Municipal Securities Rulemaking Board (MSRB).

2Between 2005 – 2018, the average transaction costs for municipal bond buy and sell trades for par value over $1 million ranged between 15 – 30 basis points. For trades where par value was $10,000 or less, the cost was much higher — often between 100 – and 250 basis points. See the MRSB report, Transaction Costs for Customer Trades in the Municipal Bond Market (https://www.msrb.org/sites/default/files/Transaction-Costs-for-Customer-Trades-in-the-Municipal-Bond-Market.pdf), July 2018, page 16.