What's Fueling the High Yield Market's Upbeat View of the Economy?

March 2023

Inflation, weaker global growth, and restrictive monetary policy look like they’ll be sticking around for a while longer. Leading economic bellweathers like the inverted US Treasury yield curve and the Federal Reserve’s internal recession indicator are signaling an elevated risk of a looming recession. Yet high yield corporate spreads remain near their 10-year average without indicating an imminent slowdown.

Investors who experienced unusual bond market volatility in 2022 may be wondering if there is stability in high yield bonds now. We sat down with Fixed Income Portfolio Manager Stephen Repoff to get his thoughts.

Q: Is the high yield corporate bond market wearing rose-colored glasses?

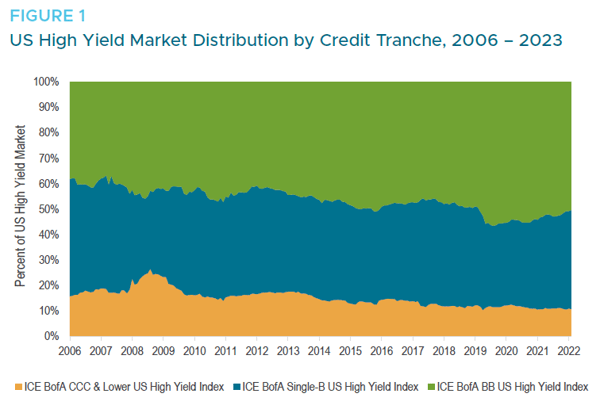

Stephen Repoff: The high yield market is reflecting a more upbeat view of the economy than US Treasuries — but there are a few key characteristics driving this view that are different from what we’ve seen in the past. First off, the average quality of the high yield market today is higher than it’s historically been, with bonds rated single-B and BB comprising a historically large share of the total market (Figure 1). Said differently, a much more substantial portion of the market used to be rated CCC or below, indicating that there was structural distress and a greater likelihood of default among large portions of it.

Source: ICE Charting. Full Market Value by rating sub-indices of the ICE BofA US High Yield Index. Tickers used are H0A1, H0A2, H0A3. Chart shows the credit quality sub-indicies found in the parent ICE BofA US High Yield Index. The full market values of H0A1, H0A2, and H0A3 were used as proxies for the market distribution, representing BB, B, and CCC & Lower qualities respectively.

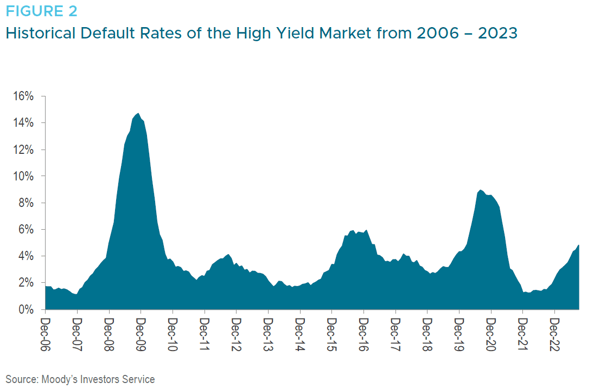

Secondly, fundamentals themselves are near, if not at, all-time highs, depending on how you measure fundamental strength. Leverage is at manageable levels after years of solid profitability and cash flow growth. The ability for companies to service their debt is also at historically high levels because we’ve had basically two and a half years of near-zero rates from the Fed, which has allowed these companies to refinance at low rates. Currently the default rate sits below historical averages (Figure 2).

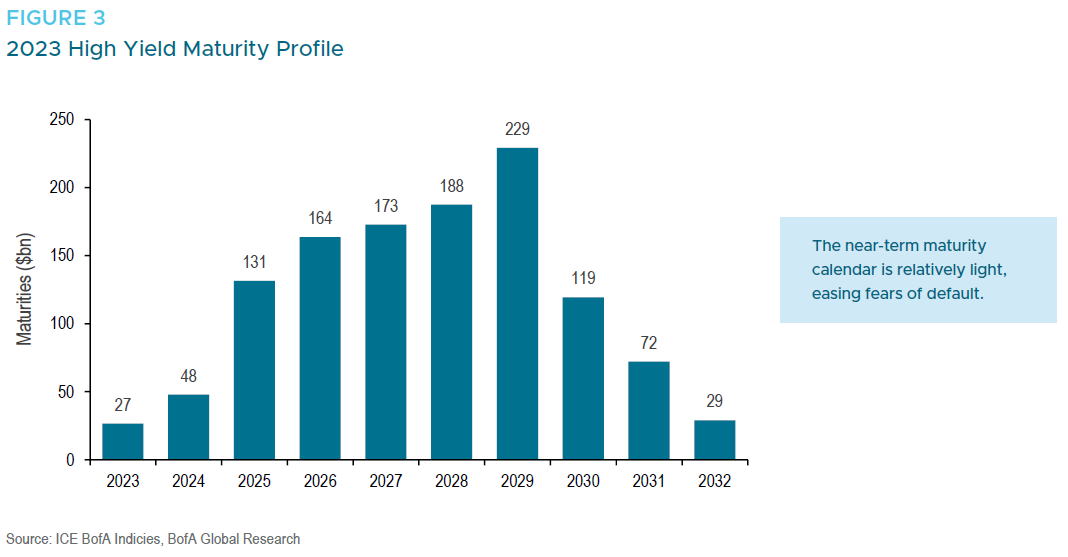

Finally, the near-term maturity calendar is relatively light as companies have taken full advantage of the opportunity the Fed provided over the last couple years to extend maturities and term out their debt (Figure 3). The overriding cause of defaults is not typically servicing debt, but rolling over debt into new financing at rates that are too onerous. However, it seems like the need for companies to raise capital over the next few years should be manageable. So we simply aren’t seeing catalysts for default like we have historically.

Related to that, one of our top concerns as active fixed income managers is to identify any companies that we hold or might consider buying that have unaddressed near-term maturities that need to be rolled over. If the market turns down just as a company needs to refinance its debt, it can be very problematic — and it’s the easiest way for investors to get in trouble with a high yield credit. If a company has gone through the last two and a half years of easy financial conditions and chosen, for whatever reason, not to refinance, that’s a kind of risk-taking for which we just don’t think there’s a reasonable level of compensation in this market. Most companies have done the right thing and pushed out maturities — not just at a lower interest rates but over many years — that it’s a net credit positive to the system.

Q: Why is the average quality of companies in the high yield debt market higher now than in previous cycles?

Stephen: We had what was effectively a mini-recession/mini-default cycle isolated to the Energy and Metals and Mining sectors back in 2015 that bottomed very early in 2016 on a valuation basis. That was a result of many years of overspending and a falling commodity price environment amid fears of a China slowdown.

These companies very successfully “found religion” after what was effectively a shareholder revolt at that time insisting that management teams needed to focus on shareholder returns. Their compensation schemes were updated to focus on return on equity and return on investment rather than growth at any cost. Since that fairly isolated credit market dynamic was fixed, we really haven’t seen anything beyond individual pockets of weakness, isolated to specific companies rather than industry-wide dynamics.

As a result, when looking at company credit profiles in the high yield universe today, we can see that margins have held up fairly well during recent market volatility. Companies came into this era with such strong balance sheets and liquidity positions, that even if we have challenges ahead of us this year, they are much better positioned to withstand them than they historically have been.

Q: Has the size of the high yield market changed meaningfully in recent years, due to companies rising to investment-grade status, or even the contrary?

Stephen: Actually, thanks to several factors, like low-issuance, maturities/calls, and upgrades, the high yield market shrank 11% last year and is forecast by some to shrink another 4-5% again this year.1 So that’s a technical tailwind: when you have fewer bonds to buy, all else equal, the price is going to go up because of the shrinking supply.

Q: What's your overall near-term outlook for the high yield market?

Stephen: While the yield curve and economists’ consensus suggest an elevated risk of recession in 2023, the relatively benign outlook implied by the high yield market is informed by improved average quality, strong credit fundamentals, and manageable near-term funding needs. We don’t anticipate any drastic changes to those inputs in he near term, and are finding opportunities in select, high-quality high yield issuers right now.

1 J.P. Morgan North America Credit Research, Credit Strategy Weekly Update, March 3, 2023